Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine and Cardiology

Prevalence of arrhythmias in a population of athletes ineligible for competitive sports activity

1Department of Sports Medicine, South Tyrol Health Authority (SABES-ASDAA), Bolzano, Italy

2Teaching Hospital of Paracelsus Medical University, Salzburg, Austria

3Medical Doctor, Genoa, Italy

4Associate Professor of Internal Medicine, University of Genoa, Italy

5Associate Professor of Sport Medicine, University of Padua, Italy

6Director of Department of Sport Medicine, South Tyrol Health Authority (SABES-ASDAA), Bolza-no, Italy

Author and article information

Cite this as

Assisi E, Libener E, Grossgasteiger S, Piaggio S, Murdaca G, Neunhäuserer D. Prevalence of arrhythmias in a population of athletes ineligible for competitive sports activity. J Cardiovasc Med Cardiol. 2026;13(01):001-008. Available from: 10.17352/2455-2976.000236

Copyright License

© 2026 Assisi E, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Abstract

The presence of arrhythmias is a frequent finding in athletes during the competitive sports medical examination, and, among those, as most often observed, we find ventricular ectopic beats (VEBs). VEBs can occur in athletes with or without heart disease, so it is of fundamental importance to identify those characteristics that give VEBs a greater risk of being associated with structural heart diseases. With this study, we wanted to analyze the prevalence of common and uncommon, sport-related ventricular ectopic beats in a population of athletes declared ineligible for competitive sports activity during the maximal ergometric test at the Sports Medicine clinic of Bolzano from 01/01/2016 to 31/05/2024, studying their morphology, complexity (couplets, triplets, NSVT), relationship with exertion and correlation with the type of sport practiced. We also analyzed the further examinations carried out following the finding of VEBs, whose outcome contributed to determining the ineligibility for competitive sports activity in patients with complex arrhythmia.

The secondary aim of the study was to evaluate the correlation between the presence of VEBs and the outcome of the second and third level examinations carried out (echocardiography, Holter ECG, magnetic resonance, coronary CT, stress echo). We wanted to evaluate the presence of underlying pathologies, highlighting the importance of the sports medical examination as a screening method to unmask asymptomatic cardiac pathologies.

Introduction

When interpreting an athlete’s ECG, common and uncommon abnormalities may be found. Among the common abnormalities, we find the early repolarization pattern, which is related to training and the heart’s remodeling response. Uncommon abnormalities are instead often linked to cardiomyopathies, channelopathies such as T-wave inversion, ST-segment depression, long QT, short QT, Brugada pattern, conduction disorders, ventricular pre-excitation, and pathological Q waves. These abnormalities require diagnostic investigations to rule out the presence of underlying pathologies [1-12].

The suspicion of an underlying pathological substrate can also derive from the detection of VEBs, documented on the 12-lead ECG, Holter-ECG, or stress tests. The ventricular ectopic beat (VEB), or extrasystole, is the simplest and most frequent form of ventricular arrhythmia. A ventricular ectopic beat is therefore an additional and abnormal heartbeat, resulting from an abnormal electrical activation that originates from one of the two ventricles, before a physiological heartbeat occurs [13-20]. It is of fundamental importance to better choose among the second and third level diagnostic tests, to state the differentiated risk characteristics presented by VEBs. The arrhythmic burden represents the number of VEBs in 24 hours and their tendency to form couplets, triplets, or non-sustained runs of ventricular tachycardia (VT). More than 500 VEBs every 24 hours on Holter monitoring can signal the risk of SCD and is a diagnostic criterion for arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. However, the number of VEBs, unlike what was previously thought, is not considered a sign of malignancy of the arrhythmia. It is an indication to carry out further diagnostic tests, as it has been shown that benign extrasystolic foci (often located in the outflow tract) can give rise to a very high number of VEBs on the 24h Holter-ECG in the absence of a pathological substrate. The morphology of VEBs is a fundamental characteristic that identifies the site of origin of the arrhythmia and represents an indispensable sign for prognostic and therapeutic purposes. To simplify it, the following classification is stated: common VEBs, which are usually idiopathic and benign, therefore associated with a structurally normal heart, and uncommon VEBs, correlated with a greater probability of underlying myocardial pathologies.

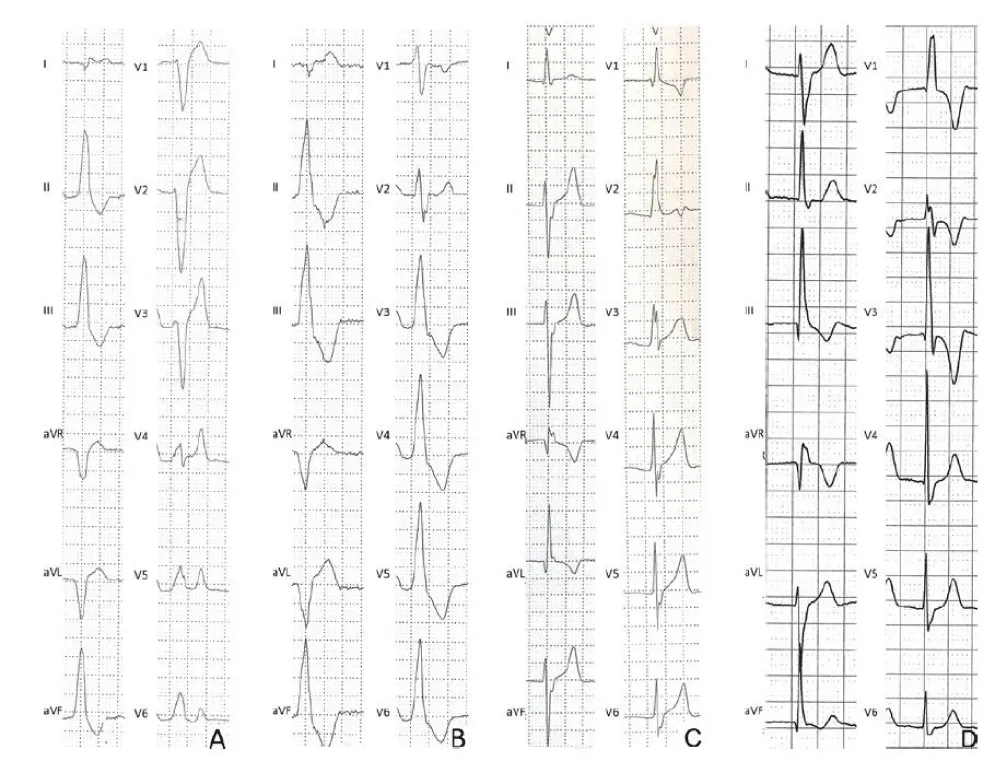

The most frequent form of common VEBs shows an ECG pattern similar to a left bundle branch block (LBBB) with an inferior QRS axis (also known as an infundibular pattern). The LBBB pattern is characterized by the negative QRS complex in lead V1, while the negative QRS complex in lead aVL and the positive QRS complex in the inferior leads (II, III, aVF) denote an inferior axis. When the ectopic QRS becomes positive beyond V3, the origin of the arrhythmia is usually located in the outflow tract of the right ventricle (RV). (Figure 1A). A similar morphology but with small R waves in V1 and the previous precordial transition (the ectopic QRS complex becomes positive for V2 or V3) often indicates the origin of the VEB from the outflow tract of the left ventricle (LV) (Figure 1B). On Holter ECG monitoring, ectopic beats usually manifest as frequent and isolated VEBs, rare couplets, but occasionally can also form triplets and runs of non-sustained VT. Typically, during a stress test, idiopathic VEBs from the RV or LV outflow tract decrease or disappear at the peak of exercise and reappear during recovery. Another pattern consistent with idiopathic and benign VEBs is the ‘fascicular’ pattern, characterized by a right bundle branch block (RBBB), superior QRS axis morphology, and QRS duration <130 ms (Figure 1C). A typical RBBB is characterized by an rSR’ pattern in lead V1 and an S wave wider than the R wave in lead V6, while the superior axis is indicated by a negative QRS in the inferior leads. This pattern characterizes an RBBB with left anterior fascicular block and indicates the origin of the VEBs from the left posterior fascicle of the left bundle branch. Rarely, VEBs originate from the left anterior fascicle and show the typical pattern of RBBB with an inferior axis, characterized by an RBBB with left posterior fascicular block (Figure 1D). The most frequent VEBs in athletes show an infundibular pattern (LBBB/inferior axis) or a fascicular morphology (typical RBBB and QRS <130 ms). These types of VEBs derive from an automatic ventricular focus and usually occur in the absence of structural heart disease. Conversely, other VEB morphologies such as LBBB with an intermediate or superior axis, which denotes an origin from the free wall of the right ventricle or from the interventricular septum, or RBBB with an intermediate or superior axis and wide QRS, which presupposes an origin from the mitral valve annulus or from the papillary muscles or from the left ventricle, are rare in athletes and when present are usually less numerous, complex (repetitive, polymorphic, with couplets) and/or induced by physical exercise and may be associated with an underlying myocardial disease. Studies on athletes undergoing CMR for the evaluation of arrhythmias show that VEBs with an RBBB morphology and wide QRS (>130 ms) often predict myocardial lesions, in particular non-ischemic myocardial scar of the LV, as evidenced by late gadolinium enhancement (LGE).

Extrasystoles are defined as polymorphic when they present at least two VEBs with different morphologies; in particular, special attention should be paid to extrasystoles under stress, with multiple morphologies, especially if the bidirectional pattern is present (morphologies that alternate with each beat), as they are associated with a high risk of SCD. The complexity of VEBs is understood as the manifestation of couplets, triplets or episodes of ventricular tachycardia on the ECG. These findings should raise the suspicion of an underlying cardiac pathology, particularly when the complexity increases during physical exercise. Furthermore, the evaluation of VEBs includes their relationship with exertion. VEBs that become less frequent or disappear with increasing exercise and load are usually idiopathic and benign ventricular arrhythmias and often have an infundibular origin (i.e., from the RV or LV outflow tract). In fact, VEBs that appear, persist or increase during the stress test are more frequently manifestations of an underlying cardiac pathology. In particular, exercise-induced VEBs with an RBBB morphology and QRS >130ms are the strongest predictors of pathological findings on CMR. Biffi, et al. have shown that the arrhythmic burden tends to decrease with deconditioning in athletes with frequent PVBs without underlying heart disease. According to this theory, PVBs may represent an epiphenomenon of the so-called athlete’s heart, that is, they are linked to the cardiac remodeling secondary to training [21-32]. However, the same group observed that with the resumption of training the arrhythmias did not reappear and that there was no correlation between the prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias and the degree of left ventricular hypertrophy secondary to training.

The presence of VEBs in athletes during a resting or stress ECG does not in itself lead to a diagnosis of cardiac pathology, but should suggest a series of further clinical and instrumental cardiovascular examinations of the first, second and third level to confirm (or exclude) cardiac pathologies. According to international criteria for the interpretation of the ECG in athletes with documented VEBs, it is indicated to perform additional tests only in the case of finding two or more VEBs in the ECG. However, it is believed that even the presence of a single VEB can justify the need for further investigations, especially in the presence of one or more of these characteristics: positive family history for sudden cardiac death or cardiomyopathies, relevant symptoms, associated ECG abnormalities, uncommon VEB morphology and presence of couplets.

First-line investigations in athletes with VEBs, in addition to history, physical examination, resting ECG and with stress test, should include 24-hour Holter-ECG including a training session (possibly with a 12-lead system to allow evaluation of the VEB morphology) and echocardiography. In athletes with negative first-level examinations, the eventual performance of further examinations is based on the characteristics of the VEBs. Athletes with a common morphology pattern do not require further tests and can be considered eligible for competitive sports, unless a high clinical suspicion of disease persists due to severe arrhythmic symptoms or a positive family history of SCD or cardiomyopathy. Athletes with an uncommon VEB pattern should undergo CMR with contrast, regardless of symptoms, family history or the results of first-level examinations, to exclude the presence of a myocardial substrate that could trigger a malignant arrhythmia during sports activity. Other examinations such as coronary CT and angiography can be considered in selected cases of master/senior athletes with exercise-induced VEBs and with a high coronary risk score. In conclusion, according to the proposed flowchart for the management of athletes with VEBs, further diagnostic evaluations with sophisticated (and expensive) imaging tests or molecular genetic tests are limited to the small subset of athletes with uncommon VEB characteristics, which may reflect a clinically hidden but potentially lethal pathological substrate, the diagnosis of which may not be detected by routine tests. On the contrary, when common VEBs are present, such as those with an infundibular or fascicular origin, reassurances should be provided to continue participating in competitive sports, provided that the first line of examinations are normal, the athlete is asymptomatic and with a negative family history of hereditary cardiac disease or SCD.

Materials and methods

In this study, patients who underwent the competitive sports eligibility visit (and were found to be ineligible) from the Bolzano archives in the period from January 2016 to May 2024 were included to investigate the presence of VEBs. To carry out this retrospective study, the data from the paper medical records kept in the archive were examined anonymously, of athletes who, having undergone a competitive sports medical examination in the province of Bolzano in the period from January 2016 to May 2024, were declared ineligible for competitive sports activity according to the COCIS 2023 protocols. The data collected come from the sports medicine clinics of Bolzano of the South Tyrolean Health Authority. The information systematically collected included personal data, data relating to the type of sport practiced, reason for ineligibility, presence of extrasystoles, data relating to the stress test, further second and third level examinations carried out and the results from the reports kept in the medical record. The stress test was performed, depending on age, with the step test or with the cycle ergometer, following a protocol of 25-50 W increments every minute and continued until physical exhaustion according to the Borg scale, regardless of the percentage of the maximum theoretical heart rate. The electrocardiograms were interpreted as normal or abnormal in accordance with the 2023 COCIS criteria. The presence of ventricular ectopic beats (VEBs) was analyzed and studied, focusing on their morphology and complexity, and classifying them as common or uncommon. The collected data were organized into a database using Excel, a program that was also used for statistical analysis, performed using pivot tables, graphs, and diagrams. The analysis was carried out using descriptive statistics, expressing the variables in numbers or frequency as a percentage.

Results

In the period from 01/01/2016 to 31/05/2024 in the clinics of Bolzano and Merano, 149,709 competitive sports eligibility visits were carried out. We have included Merano only in this statistical data as the computer program used in the clinics does not allow us to differentiate the numbers of total visits made between Bolzano and Merano. In Bolzano, 338 patients were found to be ineligible, while in Merano, 141. The difference in number is justified by a greater number of visits carried out in Bolzano compared to Merano, with a ratio of 15,000 in Bolzano and 3,000 in Merano. The percentage of ineligible patients out of the total visits carried out in the period considered is therefore 0.32%. In the subsequent analyses, only the ineligibilities from the Bolzano clinic were considered, as the medical records from Merano were not accessible. Of these 338 ineligible athletes, 33 are minors (9.8%), 305 adults (90.2%), 302 males (89.3%), 36 females (10.7%), the average age of the females was 36 (with a minimum of 11 and a maximum of 71), while that of the males is 51 (with a minimum of 10 and a maximum of 85). In particular, we have 280 adult male athletes, and 22 minor male athletes; 25 adult female athletes, and 11 minor female athletes. As for sports activity, 88 athletes (26%) practiced endurance sports, the most common of which were running and cycling, 132 (39%) practiced mixed sports, mostly tennis and football, 34 athletes (10%) practiced power activities among which the most practiced was alpine skiing, 29 athletes (9%) practiced precision sports such as bowling or archery and finally 55 (16%) held the certificate of fitness for the activity of voluntary firefighter wearing a self-contained breathing apparatus or mountain rescue. The baseline characteristics of the study population and their distribution between male and female athletes are summarized in Table 1.

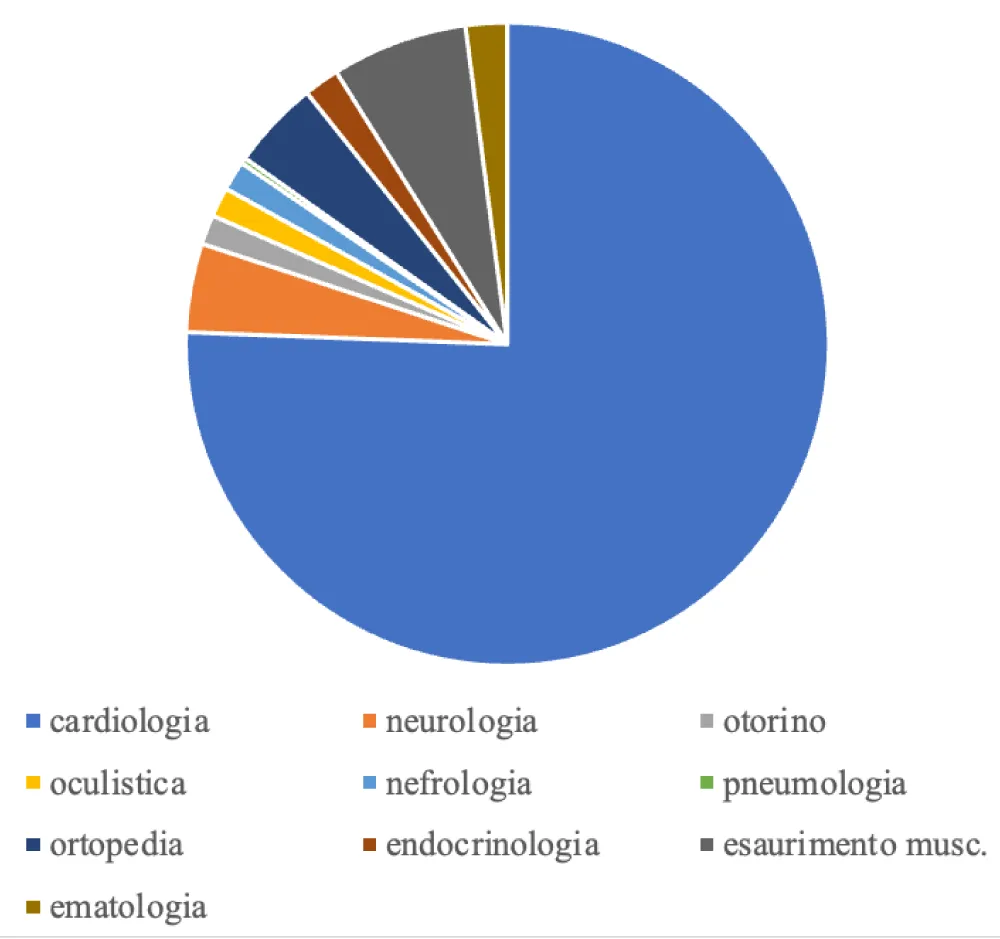

The causes of ineligibility were divided into macro categories, with the following frequencies: 258 athletes were ineligible for cardiological reasons (76%), 22 due to early muscle exhaustion, i.e. inability to finish the stress test (6.5%), 15 for neurological reasons (4%), 15 for orthopedic reasons (4%), 7 for hematological reasons (2%), 5 for otolaryngological reasons (1.4%), 5 for endocrinological reasons (1.4%), 5 for nephrological reasons (1.4%), 5 for ophthalmological reasons (1.4%) and finally 1 athlete for pneumological causes (0.2%). We have summarized the frequencies of the various causes in Graph 1.

The prevalence of VEBs within the population of ineligible patients in the years from 01/2016 to 31/05/2024 was then calculated, highlighting that within the population of 338 athletes ineligible for competitive activity, 103 had VEBs during the stress test. Of these, 99 were male (96%), and 4 were female (4%). The prevalence of ventricular ectopic beats in the population of ineligible patients from 01/01/2016 to 31/05/2024 was 30, 5%.

By calculating the prevalence of VEBs in the male population of ineligible patients in the period under examination, the following result is obtained:

In the female population, the following is obtained:

The average age of the athletes who had VEBs during the stress test was 55 ± 5 years for women and 60 ± 25 years for men. Morphology, complexity (couplets, triplets, NSVT), and relationship with the exertion of the VEBs were analyzed. The morphology of the VEBs was considered as left bundle branch block (LBBB) if the ectopic QRS complex was predominantly negative in lead V1 and as right bundle branch block (RBBB) type if the ectopic QRS complex was predominantly positive or isodiphasic in lead V1. Furthermore, we divided the VEBs according to the modern classification, thus considering the patterns similar to left bundle branch block with inferior axis and right bundle branch block with QRS<130 ms as common, and the morphologies of left bundle branch block with superior axis and right bundle branch block with QRS >130 as uncommon. The prevalence of athletes with common VEBs in the population of ineligible athletes is therefore:

The prevalence of athletes with only uncommon VEBs in the population of ineligible athletes is:

The prevalence of athletes with both uncommon and common VEBs in the population of ineligible athletes is:

As for common VEBs, 13 athletes showed a left bundle branch block morphology with an inferior axis, and 3 athletes a right bundle branch block morphology with a narrow QRS (<130ms). The uncommon morphologies occurred with the following frequencies: 21 athletes presented VEBs with a morphology similar to a left bundle branch block with a superior axis, 29 athletes had a right bundle branch block morphology with a wide QRS (<130 ms), and 37 presented polymorphic VEBs. In detail, 16 athletes presented VEBs with different morphologies from each other, but all were still considered uncommon morphologies, and 21 athletes developed both VEBs with common morphology and VEBs with uncommon morphology. The VEB morphologies are schematized in Table 2.

Analyzing our population of athletes, we arrive at the following results: 32 athletes who presented uncommon VEBs showed couplets and/or triplets of VEBs, and 6 developed NSVT during the stress test. In athletes who have common VEBs, 10 showed couplets and/or triplets, and 4 developed NSVT. Finally, among the athletes with common and uncommon VEBs, 15 showed couplets and/or triplets, and 1 developed NSVT. The complexity of the arrhythmias has been simplified in Table 3.

Subsequently, the relationship of VEBs with exertion was analyzed, exemplified below in Table 4.

In particular, in 43 athletes (42%), the arrhythmia assumed greater complexity (with couplets/triplets/runs of non-sustained VT) at heart rates higher than 85% of the maximum theoretical HR. This justifies the importance of performing a maximal stress test, as some arrhythmias may not be visible at non-maximal heart rates. In fact, according to the current COCIS 2023 guidelines, it must always be maximal (the cut-off of 85% of the maximum theoretical HR should not be considered) and monitored at least until the 4th minute of recovery. The majority of ineligible athletes who developed VEBs on the stress test were engaged in endurance sports, i.e. 47%, 19% of these athletes practiced sports defined as mixed, 13% performed sports considered to be strength sports and 12% performed sports in which the fundamental characteristic is dexterity, finally the remaining 12% of the population examined was engaged in the activity of firefighter or mountain rescue.

The medical records of the population of athletes considered so far have been examined, and the examinations that were requested after the finding of VEBs have been reported; if these were then delivered to the sports medicine clinic, and eventually their outcome. The data have been summarized in Table 6.

In 92 athletes, second-level examinations were carried out, i.e., echocardiography and Holter ECG; echocardiography was positive for structural myocardial pathologies in 77% of cases, while in the remaining cases, the echocardiography was within the normal limits. The most frequently found pathologies were mild mitral regurgitation, dilation of the aortic root, and mild and moderate aortic valve regurgitation with associated regurgitation, dilated cardiomyopathy, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The Holter ECG in 85% of the athletes confirmed the presence of arrhythmias. In 20 athletes, cardiac magnetic resonance was also performed as a third-level examination, which in 17 athletes (85%) showed pathological findings such as areas showing the presence of LGE, which therefore correspond to areas of myocyte necrosis or myocardial fibrosis. Patients who showed a strong clinical suspicion for ischemic pathologies underwent examinations such as coronary CT, carotid Doppler ultrasound, or stress echo.

Discussion

This retrospective study analyzes the prevalence of ventricular ectopic beats (VEBs) in a population of athletes found to be ineligible at the medical examination for competitive sports eligibility in the Bolzano clinic in the period from January 2016 to May 2024. The ineligibilities recorded in the Bolzano and Merano clinics were 479, i.e., 0.32% of the 149,709 total visits carried out. Subsequently, the data analysis only considered the 338 ineligibilities that occurred in the Bolzano clinic, as the medical records from Merano were not accessible. The ineligibilities occurred in 76% of cases for cardiological reasons. From the examination of the 338 medical records, it emerged that 103 athletes showed VEBs on the electrocardiographic trace of the maximal stress test. The prevalence of VEBs in the population of ineligible athletes studied was therefore 30.5%. We proceeded by studying the morphology of the VEBs, and it emerged that in 64% of the 103 athletes who showed VEBs, the latter had an uncommon morphology, in 20% of the athletes, both VEBs with common and uncommon morphology occurred, and the remaining 16% had VEBs with a common morphology. Among the morphologies considered uncommon, the most frequent was that similar to the right bundle branch block with QRS > 130 ms, in 29 athletes, and 21 athletes showed a morphology similar to the left bundle branch block with a superior axis. In 24% of the patients who had uncommon VEBs, these were polymorphic. Regarding the morphologies considered common, the prevalent one was a left bundle branch block with an inferior axis in 13 athletes, while 3 had a right bundle branch block morphology with a QRS <130. We then proceeded to study the complexity of these arrhythmias. Common morphology VEBs occurred in couplets and/or triplets in 10 athletes (60%), and in 4 (25%), they presented runs of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. Among the athletes with uncommon VEBs, in 32 cases (48%), couplets and/or triplets occurred, and in 6 (9%) runs of NSVT. Finally, among the athletes who had both common and uncommon VEBs, 15 (71%) had couplets and/or triplets, and one (4%) had a run of NSVT. In 42% of the athletes, the arrhythmia assumed greater complexity after exceeding 85% of the maximum theoretical HR, this justifies the importance of carrying out the test at a maximal level, until physical exhaustion, as some electrocardiographic anomalies tend to manifest themselves precisely at the peak of physical exertion. From the study of the relationship of VEBs with exertion, it emerged that no athlete presented VEBs only at rest, 49 athletes presented VEBs only under exertion, and 9 only in recovery. In 34 athletes, instead, they manifested both under exertion and in recovery, and finally, 11 athletes had VEBs for the entire duration of the monitoring. Considering that 42% of the athletes had VEBs during the recovery phase, the need to monitor the recovery phase up to the third minute, in a lying position on the couch, is supported.

As a secondary objective of the study, the relationship between the findings of VEBs and the further second and third level examinations carried out was evaluated, and how their results influenced the ineligibility for competitive sports of the athletes. After the finding of the complex arrhythmia, 89 athletes (86%) underwent an echocardiogram and Holter ECG, 7 (6.7%) coronary angio-CT, 2 (2%) carotid Doppler ultrasound, 1 stress echo, and 20 (19%) cardiac magnetic resonance. For 13 athletes, no further examinations were performed: 2 of these were declared ineligible because they were carriers of a loop-recorder, one because he had atrial fibrillation during the stress test, and one for the presence of a reduction in the visual field, which, regardless of the VEBs, contraindicated competitive sports activity. For the remaining 8 athletes, the requested investigations were not then delivered to the clinic, and the sufficient cause for the ineligibility was the presence of the complex arrhythmia on the ergometric test. Among the second-level examinations carried out, 76% of the echocardiograms were positive for structural myocardial pathologies; among the most frequent we found: mild mitral regurgitation, dilation of the aortic root, and mild and moderate aortic valve regurgitation with associated regurgitation, dilated cardiomyopathy, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Among the 89 Holter ECGs performed, 88% confirmed the presence of frequent extrasystoles and complex arrhythmias during the 24-hour recording. The outcome of the listed examinations, therefore, contributed to determining the ineligibility for competitive sports activity in patients with complex arrhythmia. In 20 athletes in whom the second level examinations were not exhaustive, the instrumental investigations continued with cardiac magnetic resonance, which in 17 athletes (85%) highlighted the presence of areas of myocardial tissue showing LGE, or areas of myocardial fibrosis. In summary, in 87% of the athletes who showed VEBs on the stress test, with the second and third level examinations, underlying myocardial pathologies were unmasked, which, together with the finding of the complex arrhythmia, constitute the reason for the ineligibility for competitive sports. According to the COCIS 2023 guidelines, in fact, eligibility is normally denied, even in the absence of underlying heart disease, with exceptions to be evaluated individually, in subjects with very early VEBs (R/T) and/or with close couplets and/or numerous NSVT, favored by exertion or at high frequency, and a history of sustained ventricular arrhythmia.

Conclusion

The main purpose of the competitive sports medical screening is to identify silent pathological conditions potentially at risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD). Through the presentation of the data collected in this study, the prevalence of ventricular ectopic beats in a population of athletes ineligible for the competitive sports eligibility visit is calculated. It also aims to support the recent scientific literature that highlights both the importance of the characterization of ventricular ectopic beats according to their morphology and the factors that contribute to increasing their dangerousness, and that of their study through further instrumental examinations. The presence of VEBs on an athlete’s resting ECG or during a stress test does not lead to a diagnosis of heart disease but should initiate a cascade of further cardiovascular examinations to confirm (or exclude) the presence of cardiac pathology.

The most frequently complex arrhythmias we found in our study had an uncommon morphology. 64% of patients with VEBs had an uncommon morphology, 20% both a common and uncommon morphology, and 16% had a common morphology. From the analysis of the literature, it emerges that the most frequent cause of sudden cardiac death is the onset of ventricular arrhythmias (SVT and VF), and in most cases, these events occur on a pathological substrate. Physical activity, especially if carried out at high levels, could increase the risk of developing ventricular arrhythmias and SCD. In the study by Corrado et al. conducted in the Veneto region, the relative risk (RR) of sudden death between athletes and non-athletes was found to be 2.5. It must be considered that it is not the sport that is a risk factor, but if an underlying pathology is already present, intense physical exertion can play a facilitating role for the onset of arrhythmias. Since this relationship between sport and arrhythmias is known, it is considered necessary to carry out an accurate screening on athletes to identify those latent conditions that could endanger the lives of patients.

Conflicts of interest

The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Assisi E, Libener E, Grossgasteiger S, Marine O, Naso A, Coscia F, et al. Analysis of competitive sports ineligibility in eight years of activity of the South Tyrolean provincial Sports Medicine service. Med Sport. 2024;77(1):31-6. Available from: https://doi.org/10.23736/S0025-7826.23.04261-8

- Corrado F, Zorzi A, Siciliano M. The importance of the electrocardiogram in the sports medical examination to reduce the risk of sudden death. 2011 Aug. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351903078_L'importanza_dell'elettrocardiogramma_nella_visita_medico-sportiva_per_ridurre_il_rischio_di_morte_improvvisa_RASSEGNA

- Italian Federation of Sports Cardiology (COCIS). COCIS Protocols 2023 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.aslal.it/allegati/03n%20Protocolli%20COCIS_2023.pdf

- Rugarli C. Systematic internal medicine. Milan: Edra Masson; 2015.

- Bachl N, Santilli G, Casasco M. Epilepsy and sports activity. Med Sport. 2015;68.

- Sun R, Liu M, Lu L, Zheng Y, Zhang P. Congenital heart disease: causes, diagnosis, symptoms, and treatments. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;72(3):857-60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12013-015-0551-6

- Otto CM. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of chronic mitral regurgitation. UpToDate [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/8116

- Guy TS, Hill AC. Mitral valve prolapse. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:277-92. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-022811-091602

- Maron BJ, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2013;381(9862):242-55. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(97)01282-8

- Richardson P, McKenna W, Bristow M, Maisch B, Mautner B, O'Connell J, et al. Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology Task Force on the definition and classification of cardiomyopathies. Circulation. 1996;93(5):841-2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.93.5.841

- Corrado D, Link MS, Calkins H. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra1509267

- Rigato I, Migliore F, Perazzolo Marra M, Basso C, Thiene G, et al. Diagnosis and therapy of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. G Ital Cardiol. 2006;15. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1714/1694.18506

- Ammirati E, Frigerio M, Adler ED, Basso C, Birnie DH, Brambatti M, et al.. Management of acute myocarditis and chronic inflammatory cardiomyopathy: an expert consensus document. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13(11):e007405. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/circheartfailure.120.007405

- Imazio M, Gaita F, LeWinter M. Evaluation and treatment of pericarditis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015 Oct 13;314(14):1498-506. Erratum in: JAMA. 2015 Nov 10;314(18):1978. Erratum in: JAMA. 2016;315(1):90. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.12763

- Grover G. The definition of myocardial ischemia. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;29(1):141. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0008-6363(95)90114-0

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018 Sep 1;39(33):3021-3104. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2019;40(5):475. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339

- Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(14). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.054

- Myerburg RJ, Castellanos A. Sudden cardiac death. In: Braunwald E, editor. Heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. New York: Saunders; 1997. p. 742-779.

- Steriotis AK, Nava A, Rigato I, Mazzotti E, Daliento L, Thiene G, Basso C, Corrado D, Bauce B. Noninvasive cardiac screening in young athletes with ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(4):557-62. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.10.044

- Drezner JA, Sharma S, Baggish A, Papadakis M, Wilson MG, Prutkin JM, et al. International criteria for electrocardiographic interpretation in athletes: consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(9):704-731. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-097331

- Antonelli A, Montenero AS. Benign ventricular extrasystole. Available from: https://www.scribd.com/document/400202271/Bev-Benigna

- Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) – Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/premature-ventricular-contractions/symptoms-causes/syc-20376757

- Corrado D, Drezner JA, D'Ascenzi F, Zorzi A. How to evaluate premature ventricular beats in the athlete: critical review and proposal of a diagnostic algorithm. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(19):1142-1148. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-100529

- Morshedi-Meibodi A, Evans JC, Levy D, Larson MG, Vasan RS. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of exercise-induced ventricular premature beats in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;109(20):2417-22. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000129762.41889.41

- Biffi A, Pelliccia A, Verdile L, Fernando F, Spataro A, Caselli S, et al.. Long-term clinical significance of frequent and complex ventricular tachyarrhythmias in trained athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(3):446-52. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01977-0

- Heidbüchel H, Hoogsteen J, Fagard R, Vanhees L, Ector H, Willems R, et al.. High prevalence of right ventricular involvement in endurance athletes with ventricular arrhythmias. Role of an electrophysiologic study in risk stratification. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(16):1473-80. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00282-3

- Selzman KA, Gettes LS. Exercise-induced premature ventricular beats: should we do anything differently? Circulation. 2004;109(20):2374-5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000128241.01086.9c

- Biffi A, Maron BJ, Verdile L, Fernando F, Spataro A, Marcello G, et al.. Impact of physical deconditioning on ventricular tachyarrhythmias in trained athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(5):1053-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.065

- Biffi A, Maron BJ, Culasso F, Verdile L, Fernando F, Di Giacinto B, et al.. Patterns of ventricular tachyarrhythmias associated with training, deconditioning and retraining in elite athletes without cardiovascular abnormalities. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(5):697-703. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.049

- Sheikh N, Papadakis M, Ghani S, Zaidi A, Gati S, Adami PE, et al.. Comparison of electrocardiographic criteria for the detection of cardiac abnormalities in elite black and white athletes. Circulation. 2014;129(16):1637-49. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.113.006179

- Calore C, Zorzi A, Sheikh N, Nese A, Facci M, Malhotra A, et al. Electrocardiographic anterior T-wave inversion in athletes of different ethnicities: differential diagnosis between athlete's heart and cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(32):2515-27. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv591

- Vöhringer M, Mahrholdt H, Yilmaz A, Sechtem U. Significance of late gadolinium enhancement in cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR). Herz. 2007;32(2):129-37. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-007-2972-5

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley